Exercise prescription for the treatment and prevention of osteoporosis

What is osteoporosis?

Osteoporosis is a metabolic bone disease characterized by skeletal fragility and susceptibility of fracture due to a loss of bone mass and changes in the structure of bone tissue. It affects over 200 million people worldwide, causing 1.3 million fractures per year. The most common sites of fractures include the vertebrae, hip, and wrist. 1

Osteoporosis can lead to pain, making it harder to move around. This can result the loss of independence and an increased risk of health complications, even death.2

Who is most susceptible?

Osteoporosis affects men and women of all races and ethnicities. However, it is more prevalent in non-Hispanic white and Asian women, and postmenopausal women are particularly susceptible this disease. In the US and Europe, osteoporosis affects an estimated 30% of postmenopausal women, with a concerning 40% of these women likely to experience fractures in the future.2

How is it diagnosed?

A dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) test is most used for measuring bone mineral density. During the DXA scan, you lie comfortably on a padded table while a scanner using minimal x-rays passes over your body. This fast and painless scan checks your bone mineral density (BMD), with a special focus on areas like the hip and spine.3

The results of your BMD test will be compared to the average bone density of young, healthy people, and to the average bone density of other people of your age, sex, and race. You may be diagnosed with osteoporosis if your BMD falls below a certain threshold.3

What are risk factors associated with osteoporosis?

Table 1

Risk Factors for Osteoporosis or Decreased Bone Mineral Density

| Inherited Factors | Environmental Factors |

| Caucasian or Asian | Low body weight |

| Female | Loss of menstrual function |

| Osteoporotic fracture in a first-degree relative | Poor nutrition / low calcium intake |

| Height <67in. (170cm) | Inactivity |

| Weight <127lb (58kg) | Prolonged corticosteroid use |

| Smoking | |

| Excessive alcohol intake | |

| Caffeine |

From Ehrman et al., 2009 4

What can you do to support bone health?

You can support bone health by improving your lifestyle habits. Reducing your consumption of caffeine and alcohol, quitting smoking, eating a healthy diet with sufficient calcium, increasing your physical activity, and engaging in regular exercise.

Exercise & osteoporosis

Engaging in regular exercise is vital for not only for improvements in bone strength, but to reduce the risk of falls and the impact a fall would have on the body should one occur. A meta-analysis of 15 randomized control trials found that fall-related fractures were reduced by 40% in adults 50 years of age and older who took part in regular exercise training.5

As outlined by Daly et al., 2019, studies on animals have revealed several key factors that influence how bones adapt to mechanical stress. These factors include:

- Dynamic and intermittent loads: Bones respond better to forces that come and go, rather than constant pressure.

- High-magnitude and rapid loads: Bones benefit more from strong and quick impacts compared to weaker ones.

- Varied loading directions: Bones adapt more effectively when forces come from different angles and directions, not just one.

- Limited loading cycles: A smaller number of loading cycles can be more stimulatory for bone growth than many repetitions, so long as adequate intensity is achieved.

Exercise prescription

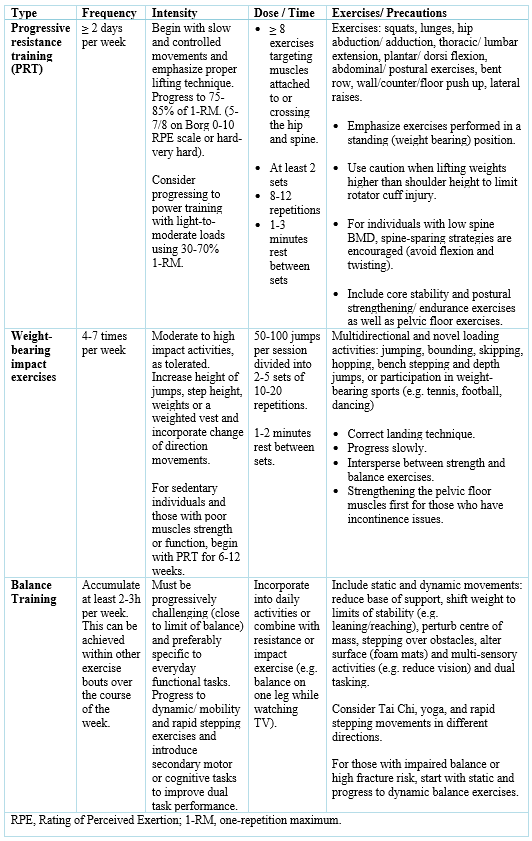

Table 2

Exercise for osteoporosis prevention

Adapted from Daly and Giangregorio, 2019 6

Table 3

Exercise for those with osteoporosis

From Ehrman et al., 2009 4

References:

1. Wong, S., Chin, K.-Y., Suhaimi, F., Ahmad, F., & Ima-Nirwana, S. (2016). The Relationship between Metabolic Syndrome and Osteoporosis: A Review. Nutrients, 8(6), 347. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8060347

2. Daly, R. M., Dalla Via, J., Duckham, R. L., Fraser, S. F., & Helge, E. W. (2019). Exercise for the prevention of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: an evidence-based guide to the optimal prescription. Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy, 23(2), 170–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjpt.2018.11.011

3. Garrick, N. (2022, December). Osteoporosis. National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. https://www.niams.nih.gov/health-topics/osteoporosis/diagnosis-treatment-and-steps-to-take

4. Ehrman, J. K., Gordon, P., Visich, P., & Keteyian, S. (2009). Clinical exercise physiology (2nd ed., p. 487). Human Kinetics

5. Zhao, R., Feng, F., & Wang, X. (2016). Exercise interventions and prevention of fall-related fractures in older people: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. International Journal of Epidemiology, 46(1), dyw142. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw142

6. Daly RM, Giangregorio L. Exercise for osteoporotic fracture prevention and mangement. In: Bilezikian JP, ed. Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism. 9th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2019:517-525.

Leave a comment